One of the most politically charged works in the workshop was a performative and processual engagement that began before the workshop. One of the artists offered to stamp the currency notes of anyone who volunteered with the words FREE CHINA FREE TIBET, in bold red letters. Inspired by Tibetan activist Tenzin Tsundue’s writing, the slogan questioned the idea that only Tibet was colonised through a control of its territory, economy and culture. Colonisation of the mind, the lack of freedom and omnipresent surveillance and censorship eliminates the freedom of supposedly independent citizens of a country, in this case China. Intended to generate questions and conversations on the notion of freedom and autonomy, the stamped notes resulted in furious debates and anxiety (for the participants of the workshop who had voluntarily got their currency stamped) over factors ranging from the monetary value of the notes being voided due to the presumed illegality of defacing currency, to the possibility of implicating local Tibetans in the act once the money circulated in the market. The slippery question of legality and the potency of currency as one of the primary markers of an independent state were central to the reaction of local Indians, one of whom considered the stamp across a five hundred rupees note as an insult to Gandhi, the ‘father of the nation’. Tibetans, while identifying and supporting the cause of a Free Tibet, were usually resistant to the idea that the people of China too were perhaps victims of autocratic state policies. In the spirit of the nomadic workshop which encourages participants to engage with the specific context of a place, the currency project was the most audacious and precarious. While rooted in complete sympathy with the contemporary condition of Tibetans in Tibet and in exile, it opened up ways to think about nationhood, the desire for it, as well as the apparatus of nations, the relationship between China, Tibet and India in a performative, open-ended way, which while running the risk of legal and political crackdown, forced all the participants- in the workshop as well as the larger community into which the currency notes were introduced and circulated- to examine their own position and politics, sans sentimentality.

During the two-week workshop, there was news filtering in as word of mouth almost every other day of yet another self immolation within Tibet. On the 5th of November 2012, Jamyang Norbu wrote that there had been seventy self immolations in Tibet . Until today, more than a hundred men and women have doused themselves with inflammable liquid, pouring it over every inch of their bodies, knowing that the single spark will turn them into infernos. There are negligible mainstream media reports (barring a few stray articles) in India and abroad about the self-immolations. In March 2012, 27 year old Jamphel Yeshi set himself on fire in Delhi. The image of Yeshi engulfed in flames as he ran through the crowds in Jantar Mantar was replicated in the media, in posters and banners. Ayisha Abraham’s response to this devastating form of protest and resistance was a very personal one. She wrote,

“The immolations in Tibet have been relentless since we arrived.

I stare at them; those small printouts pasted on walls, of charred distorted bodies,

as though Pompei had spewed more volcanic ash.

Caught in agonizing gestures. Frozen angst.

Trophies for unrequited politics. Or freedom.”

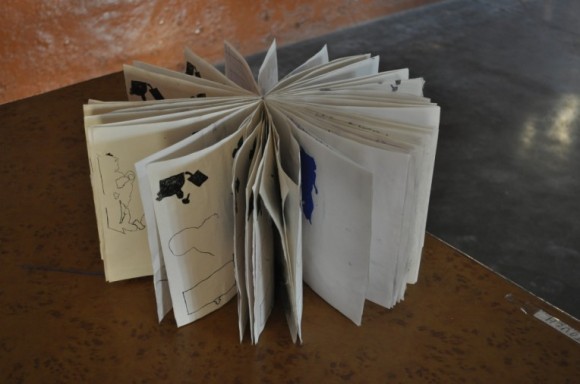

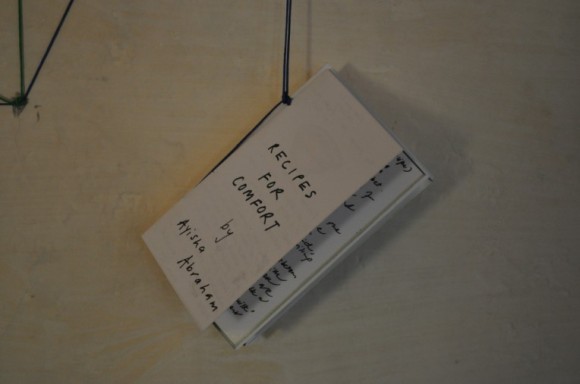

On rough sheets of paper that she made in the open field, Ayisha screen printed image after image of Jamphal Yeshi’s running body, engulfed in fire, the paper itself containing traces of the history, landscape and her response to the place where it was made. She also recorded recipes of the local Tibetan food that she was eating, each accompanied by a painted illustration of the dish. These were compiled into a small booklet entitled, ‘Recipes for Comfort’. The banal rituals of the everyday were offered as a counterpoint or a balm as it were; “I must throw that splash of cool blue-cerulean and turquoise, over the page, as though to cool those burning bodies, as though to feel the blue sky caress the hot red of burning timber.”

‘Sacred Heart’, Munkhtsetseg Jalkhaajav (Mugi)’s mixed media work, installed in a room at TIPA, consisted of collage paintings on paper and a Khatag Heart, constructed out of honorific white silk scarves. In McLeodganj, she displayed it suspended over a bowl, the still waters of which bore the reflection of the heart as a lotus, an image drawn from traditional Mongolian medical texts that liken the human heart to a lotus. On her return to Ulaanbaatar, the work continued. ‘Sacred Heart’ was transformed for Mugi into ‘Tibetan Heart’. On reading about the increasing numbers of self immolations, in an tremendously moving performative gesture, she set the fabric heart on fire, against the backdrop of the snow covered mountains in Mongolia. She wrote that in Dharamsala, the work had been connected to water; it was now connected to fire. Inflicting the act of violence upon her work, reducing it to ashes lying on the snow, Mugi felt the work was finally complete.

Karma Sichoe, an exile Tibetan artist living in Dharamsala trained as a traditional tangkha painter. During the workshop, he proposed collective action, albeit through voluntary participation, to clear a part of Dharamsala of rubbish. He chose the kora, the circumambulatory path around the Dalai Lama’s temple; the narrow trail winds through a sun-speckled forest and is used by almost all pilgrims, whether Buddhist or not. The path is littered with the residue of consumption and reverence- scraps of burnt prayer flags, votive objects, photographs, used plastic bottles, ubiquitous multi coloured plastic carry bags and sweet wrappers. Waste, once ‘use’ is vacated from it, is imbued with the idea of pollution. For the artists and the strangers who joined Karma in the act of collecting trash from the kora, turned into a reverential action; the path was cleaned and the sides were white washed, in a symbolic act of re-purification. Karma went through the many sacks of waste and separated bits from which he later created a ‘trash mandala’ in a tangkhas format.

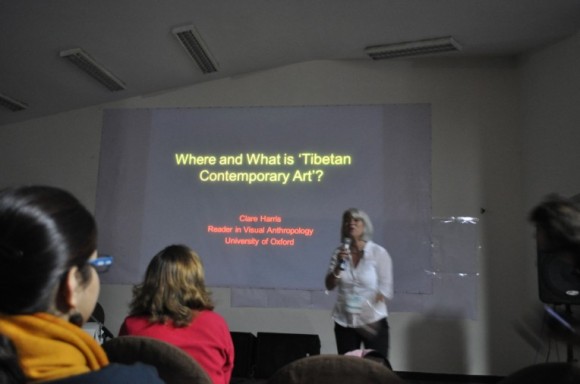

Is it possible to creatively re-imagine ‘Tibet’? The contemporary reimagining of tradition runs the risk of become a formulaic trope, where religious icons are re-garbed as ‘pop’, in visual and material form. Perhaps, innovate creative strategies that have the audacity to imagine a future that is able to transcend the by-now clichéd debate tradition and contemporaneity are required. The Dharamsala workshop over an intense two weeks was an example of how a temporary zone of action can be created. It is in the ephemerality, in the tentativeness of the proposals rather than prescriptive long term ‘solutions’ that the success of the workshop lay. For a community in exile, it may be that effective action lie in temporary tactics, in which place, language and histories can be reclaimed through contemporary strategies.